“Husband of One Wife”: Celibacy and the Diaconate

When my wife tells her friends that I’m preparing for ordination as a deacon, the detail they tend to fixate on the most is that, once…

When my wife tells her friends that I’m preparing for ordination as a deacon, the detail they tend to fixate on the most is that, once ordained, I won’t be able to remarry. Oddly enough, my male friends never ask me about that. But her friends seem genuinely concerned about what will happen should she die before me. Who will help me take care of the kids? Won’t I get lonely? And why is it any of the Church’s business if I remarry?

Clerical Celibacy the Norm

Let’s address that last question first. While the idea of deacons not being able to remarry seems strange to those unfamiliar with the practice of celibacy in the Church, it’s really not that unusual. Deacons are clerics*, and the Christian norm is that clerics may not marry. Either they are unmarried when they enter the clerical state and remain that way; or, if married, they promise to not remarry should their wives predecease them.

*Clerics are those who have received holy orders — bishops, priests and deacons. One enters the clerical state with ordination to the diaconate.

Consider global Christianity. The Roman Catholic Church is the largest Christian Church with over 1.2 billion members, over half of the world’s Christian population. The practice in the Roman Church is that married men may be ordained to the diaconate, while only unmarried men can be ordained to the priesthood or as a bishop (sometimes exceptions are made for the priesthood). Once ordained, however, a cleric cannot get married.

That’s the western tradition. In the east, there are 22 churches sui iuris that are in union with the Catholic Church and some 15 autocephalous Eastern Orthodox churches, as well as a handful of other autonomous eastern churches. In all of these, married men may be ordained to the diaconate and priesthood, but only celibate men are chosen to be bishops. So married priests are much more common in the east than in the west. Again, however, once ordained, clerics cannot marry.

In both east and west, there is a strong monastic tradition where lay men and women decide to forsake marriage and live celibate lives devoted to prayer and often other forms of service, such as preaching, teaching, ministering to the sick and poor, etc. I mention this monastic tradition as another example of the importance of celibacy in the Church.

Viewed in the greater context of Christian history and tradition, the fact that Protestant clergy can marry is a bit of a novelty. The practice was a 16th century innovation by Martin Luther, who as an Augustinian monk decided to marry a Benedictine nun, both abandoning their vows of celibacy. (Protestants have also largely abandoned monasticism). While Protestants make up the majority of Christians in the United States, world-wide they make up only about 36.7% of Christians. That’s at present. If we expand our scope to the entire 2000 year history of the Church, the Protestant custom of allowing clergy to marry is in the definite minority.

Seen in this broader context, the fact that married Roman Catholic deacons cannot remarry if their wife predeceases them falls in line with the normal practice of clerical celibacy. In other words, it’s not that unusual.

(As an aside, some mistakenly believe that if the Roman Catholic Church were to change her discipline to allow married priests, it would mean “priests could get married” as in the Protestant tradition. In fact, were that to happen, it would mean married men would be eligible to be ordained to the priesthood, as they are in the East. But, just like Eastern priests today, and deacons in the East and West, once ordained they would not be able to marry.)

Why Celibacy?

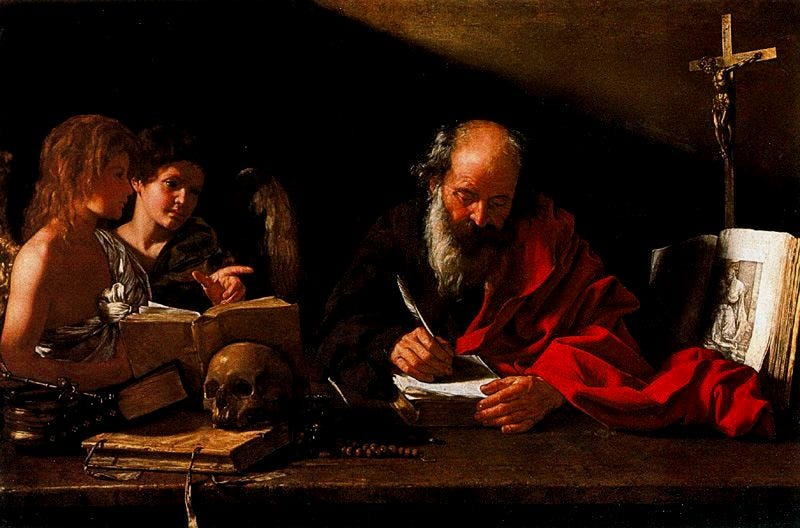

But why celibacy in the first place? This article is not intended to be an apologetic defense of clerical celibacy, but suffice to say it has Biblical roots. Consider 1 Corinthians 7, where St. Paul expresses the desire that all might be celibate like him.

“Are you free from a wife? Do not seek marriage. . . those who marry will have worldly troubles, and I would spare you that. . . . The unmarried man is anxious about the affairs of the Lord, how to please the Lord; but the married man is anxious about worldly affairs, how to please his wife, and his interests are divided. And the unmarried woman or girl is anxious about the affairs of the Lord, how to be holy in body and spirit; but the married woman is anxious about worldly affairs, how to please her husband” (1 Cor 7:27–34).

Of course the preeminent model of celibacy is Jesus Christ. In the gospels, Jesus refers to those who have forsaken marriage “for the sake of the kingdom” (Mt 19:11–12). He refers to this call as a gift that is granted to some, but not everyone. Christian clerics don’t forsake marriage because it is viewed as lowly, but as witness to their commitment to something even higher. As good as marriage is, certain men and women are called to forgo that good for the sake of something greater.

Even from Biblical times, married leaders in the Church were called to be husbands “to one wife” (1 Tim 3:2). In other words, should their wife die, they would not marry again. They would would then devote themselves fully to the ministry of the Church, as celibate clerics.

(For some very practical reasons why a celibate clergy is a good idea, click here).

But What About the Children?

The concern most people express when they hear that I will not be able to remarry is what will happen if my wife dies while our children are still young?

This is certainly a consideration. Let’s imagine that my wife tragically dies while the kids are still small, and that there are no restrictions on my remarrying. What would happen then?

It’s not as if I have a back-up wife waiting in the wings. I may spend years in the grieving process before I’m ready to even think about dating anyone else. It may take years more to meet the right woman (and as my wife joking says, “Who’d take you with six kids in tow — you don’t make that much money!”). Then we’d have to date for a while and build a relationship before moving towards marriage. That would all take time. And that’s if I even wanted to remarry, and if I met the right person. Those are big “ifs.”

Meanwhile, I’d need help with the children immediately. How would I manage? I’d rely on my parents and my in-laws, all of whom, thankfully, live fairly close by and are in good health. I’d rely on our older children to help care for the younger ones (there is a 13 year span between our oldest and youngest). I’d rely on friends and extended family. I’d rely on our parish community. I would expect all of these good people to help support me in my time of need. Even if I could remarry.

But once I’m ordained a deacon, I won’t be able to remarry. So what would change in the immediate aftermath of my wife’s untimely death? Not a thing, really. I’d still need immediate help. And I’d still rely upon my family, friends and church community to support me.

Moreover, the idea of me needing to find a new wife to “help with the kids” is a bit insulting to wives everywhere. It implies that their main role is to do the laundry and change the diapers. Having a wife is about having a best friend and life partner. If all I need is help with the kids, I can hire a nanny.

Loneliness

What concerns me more is not the thought of my wife’s sudden demise while the kids are still young, but what would happen should I lose her later on when we are empty-nesters (which is statistically much more likely). I’m an introvert and value my alone time (all the more because of its scarcity in a house with six children). But the prospect of living out my retirement years by myself, without my best friend, is not appealing.

But here’s the thing. I won’t be by myself. You know those six kids I have? I suspect they will give me a ton of grand-kids. And they will all need help from their dear-old deacon grandpa, just like my wife and I rely on our parents to help us raise our children. I anticipate spending a lot of my days with grandchildren on my lap and my adult children and their spouses by my side. Looking at them will remind me of my wife and all the joy that she brought into my life that still continues on through our growing family. That doesn’t sound too bad.

I’d certainly miss her. But that’s just it. I won’t miss “having a wife.” I’ll miss her. My life-partner. The mother of my children. The one who has helped to form me throughout my adult life. I’ll miss her. The freedom to remarry wouldn’t make that hurt any less. If anything, not marrying again will make my relationship with my wife all the more special. She’s my one, and always will be.

For the Sake of the Kingdom

Finally, let’s not forget Who I am seeking ordination for, after all. My whole reason for doing this is to draw closer to Christ, and I know that I will have Him there by my side whatever may come.

I have heard it said that part of every celibate priest longs for the married life, and part of every married man longs for the solitude of the monastery. Should my wife predecease me — and if that happens, I pray it is a long, long time from now — I would like to think I would spend my solitude in prayer and study. This is the model given us by the holy widows, after all, who would devote so much of their time to worship in the Temple.

Though alone in human terms, I know I would be surrounded by the saints and angels, joining their prayer to mine as I await the day when my wife and I will be reunited, with all the saints, before our Lord.