“If I do not wash your feet, you will have no part with Me.”

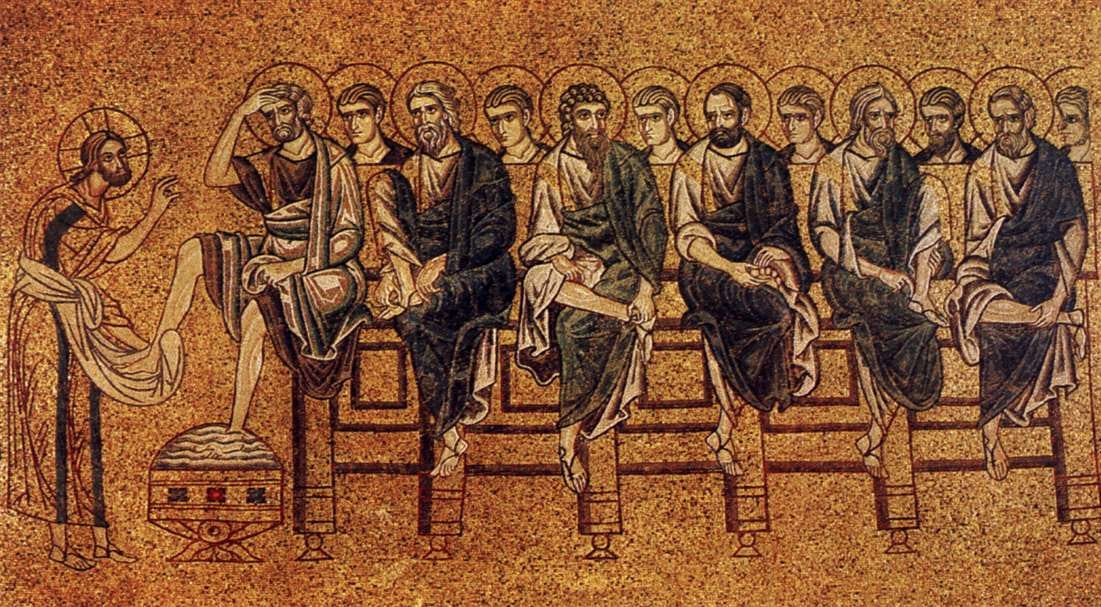

The establishment of the diaconate in the washing of the Apostle’s feet.

The establishment of the diaconate in the washing of the Apostle’s feet.

I recently finished reading the 2002 report of the International Theological Commission (ITC), From the Diakonia of Christ to the Diakonia of the Apostles. This is an historico-theological research document tracing the history of the diaconate from the time of Christ until now. I recommend it as required reading for any deacon or deacon candidate.

One thing that took me by surprise, though, was the claim in the report that Acts chapter 6 does not describe the establishment of the diaconate. This is where we find the story of the “choosing of the seven.”

At that time, as the number of disciples continued to grow, the Hellenists complained against the Hebrews because their widows were being neglected in the daily distribution. So the Twelve called together the community of the disciples and said, “It is not right for us to neglect the word of God to serve at table. Brothers, select from among you seven reputable men, filled with the Spirit and wisdom, whom we shall appoint to this task, whereas we shall devote ourselves to prayer and to the ministry of the word.” The proposal was acceptable to the whole community, so they chose Stephen, a man filled with faith and the holy Spirit, also Philip, Prochorus, Nicanor, Timon, Parmenas, and Nicholas of Antioch, a convert to Judaism. They presented these men to the apostles who prayed and laid hands on them (Acts 6:1–6).

I have always heard these seven referred to as “the first deacons.” So I was surprised, and intrigued, when the International Theological Commission proclaimed, “[I]n the Acts of the Apostles 6:1–6 it is not the institution of the diaconate that is being referred to” (ch 2, I, 2).

Not that the esteemed theologians discount what is going on in Acts 6. In a footnote to the above statement, they specifically speak of the laying on of hands as signifying ordination (and not merely an appointment or blessing). But this does not necessarily make what is happening here the origin of diaconal ministry.

This uncertainty is nothing new. In another footnote (235), the ITC shows that this debate goes back to the patristic era. St. Ireneaus was of the opinion that Acts 6 marked the beginning of the diaconate, while St. John Chrysostum did not believe the seven to be deacons. Regarding where the debate stands now, the ITC calls the idea that the choosing of the seven represents the institution of the diaconate “a minority [opinion] today” (Ch 7, II, 1).

But if the diaconate was not established in Acts 6, when was it established? The ITC mentions another possibility — when Jesus washes the feet of the Apostles during the Last Supper (Ch 7, II, 1).

…during supper, fully aware that the Father had put everything into his power and that he had come from God and was returning to God, he rose from supper and took off his outer garments. He took a towel and tied it around his waist. Then he poured water into a basin and began to wash the disciples’ feet and dry them with the towel around his waist. He came to Simon Peter, who said to him, “Master, are you going to wash my feet?” Jesus answered and said to him, “What I am doing, you do not understand now, but you will understand later.” Peter said to him, “You will never wash my feet.” Jesus answered him, “Unless I wash you, you will have no inheritance with me.” Simon Peter said to him, “Master, then not only my feet, but my hands and head as well.” (John 13:2–9)

What does the washing of the feet have to do with the diaconate? Well, diakonos means “servant,” and the washing of the Apostles’ feet is the preeminent sign of Jesus’ humble service. Moreover, this action takes place during the Last Supper, widely recognized as the establishment of the Eucharist as well as the priesthood, those two sacraments going hand in hand. But of course there is no “sacrament of the priesthood.” There is the one sacrament of Holy Orders.

The sacramental grace of the priesthood was given to the Apostles at that time. But the Apostles were not merely priests. They would have possessed the fullness of the sacrament of Holy Orders, which includes the episcopacy, the priesthood — and the diaconate.

Sacramental Ministry

This is important to our understanding of the diaconate as a sacramental ministry. Another thing I was surprised to learn from the ITC’s document was that the sacramentality of the diaconate was not always taken for granted. While the ITC clearly comes down on the side of the diaconate being a sacramental ministry —as it is regarded in the Code of Canon Law and the Catechism of the Catholic Church, by Vatican II and the Council of Trent — this was not always so clearly understood.

To see where the confusion might have arisen, one must remember that prior to 1972, there existed a cursus honorum through which men seeking ordination in the Catholic Church passed. This began with receiving tonsure (the mark of the clerical state). One then became a porter, a reader, an exorcist, an acolyte, a subdeacon, a deacon, and finally a priest.

The orders from acolyte down were considered “minor orders,” while the orders from subdeacon up were considered “major orders.” It was universally understood that the priesthood was a sacrament. And it was universally understood that the minor orders were not. But as to the diaconate and subdeaconate there was debate within the Church.

It is easy to see why some might not consider the diaconate as a sacrament. When one is ordained to the priesthood, one is imbued with certain potestas or “powers.” The priest can consecrate the Eucharist. The priest can hear confessions. The priest can anoint the sick. What is the potestas of the deacons? Nothing. A deacon cannot effect any sacrament that a layman cannot. (But what about baptisms and marriages? Even a layman can administer baptism in an emergency; and in marriage it is not the minister who confers the sacrament, but the bride and groom).

Without specifically defined potestas, many doubted whether the diaconate should rightfully be understood as a sacramental ministry rather than a delegated ministry. There is no need to go into those debates here (read the ITC’s document), but suffice it to say the Church’s Magisterium has since Trent clearly taught that the diaconate is a part of the sacrament of Holy Orders. Thus we have our current teaching, universally recognized today, that the sacrament of Holy Orders consists of three orders which make up one sacrament (kind of like the Trinity in a way — pretty cool, huh?).

Holy Orders is the sacrament through which the mission entrusted by Christ to His Apostles continues to be exercised in the Church until the end of time: thus it is the sacrament of apostolic ministry. It includes three degrees: episcopate, presbyterate, and diaconate (CCC 1536).

A Sign Instituted By Christ

What does any of this have to do with when and how the diaconate was established? Let’s recall for a moment our catechism definition of a sacrament.

The sacraments are efficacious signs of grace, instituted by Christ and entrusted to the Church, by which divine life is dispensed to us (CCC 1131).

A sacrament, by definition, is instituted by Christ. If we look to Acts 6 as the establishment of the diaconate, then it would be hard to say that the diaconate was instituted by Christ. What we see in Acts 6 is the Apostles acting with authority given then by Christ to designate seven men to a particular ministry of service, and convey that authority to them by the laying on of hands. All of this certainly sounds like the diaconate — and it undoubtedly is, in my mind.

But if we are to properly understand the sacramental nature of the diaconate, then we must understand it as something instituted by Christ, and not by the Apostles on their own initiative. In other words, the Apostles cannot pass on anything they did not themselves receive from the hands of Christ. It seems a strong argument could be made that the ministry of diaconal service was given by Christ to the Apostles as He washed their feet at the Last Supper.

When Peter initially refuses to have his Master serve him, Jesus tells Peter flatly, “If I do not wash your feet, you will have no part with me” (Jn 13:8).

The washing of guests’ feet was a task normally done only by a slave. What Jesus is giving to the Apostles is the example of service without limits. The Son of God, who had already humbled Himself to take the form of a man also takes the form of a slave (Phil 2:7). He would humble Himself even further by dying on the cross for us. He tells the Apostles, if they do not humbly serve others as He serves them, they can have no part (no share) with Him.

What is ordained ministry but receiving a share of Christ’s Spirit to serve others as He serves?

On the night Jesus gave us the Eucharist, He also instituted the priesthood. But as we mentioned above, the priesthood is one of three orders that make up the one sacrament of Holy Orders. Perhaps what Jesus gave the Church on that night was the fullness of this sacrament — bishop, priest and deacon.

Then the Apostles, possessing in themselves the fullness of this sacrament, would then be able to pass that sacramental grace on to others to serve the Church as bishops (overseers), priests (elders), and even humble deacons (servants). In fact, we see them doing exactly that in the Acts of the Apostles. The bishops having the fullness of the sacrament; the priests and deacons having a lesser share in order to assist the bishop in apostolic ministry.

Understood in this way, what we read in Acts 6 is not the Apostles instituting a new diaconate, but ordaining men to a share in the ministry of service (diakonos) that they received from Christ at the Last Supper.