Is Christmas Pagan?

Bethlehem smells wonderful. Out of all the places we visited in the Holy Land during our recent pilgrimage, the denizens of Bethlehem…

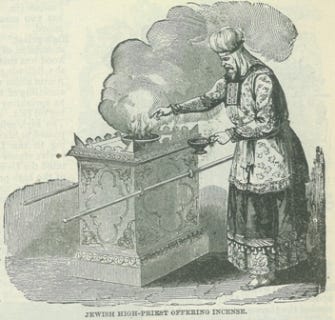

Bethlehem smells wonderful. Out of all the places we visited in the Holy Land during our recent pilgrimage, the denizens of Bethlehem seemed to make the most use of incense. It seemed that every other shop had a small censer burning by their entrance, filling the sidewalks with heavenly scent.

While we were walking through the Bethlehem streets, one of my fellow pilgrims, a woman from a parish just one town over from mine, approached me. “I have a friend,” she said, “who keeps saying incense is pagan and Christians shouldn’t use it. What can I tell her?”

“Tell her to look at the beginning of Luke’s gospel,” I advised. Zechariah, the father of John the Baptist, was a priest. And part of his duties as a priest was to burn incense. In fact, this is exactly what he was doing when the angel Gabriel appeared to him, announcing his wife would conceive and bear a son.

“Once when he was serving as priest in his division’s turn before God, according to the practice of the priestly service, he was chosen by lot to enter the sanctuary of the Lord to burn incense. Then, when the whole assembly of the people was praying outside at the hour of the incense offering, the angel of the Lord appeared to him, standing at the right of the altar of incense. Zechariah was troubled by what he saw, and fear came upon him” (Lk 1:8–12).

Priests would offer incense twice a day in the Temple, during hours of prayer in the morning and in the evening (see Exodus 30:7–8). Burning incense during prayer as an offering to God is not something Catholics appropriated from pagan cultures. Rather, it is something we inherited from our Jewish forebears. Christians have been burning incense during prayer for as long as there have been Christians.

There’s even going to be incense in heaven! At least according to St. John’s vision, recorded in Revelation.

“And another angel came and stood at the altar with a golden censer; and he was given much incense to mingle with the prayers of all the saints upon the golden altar before the throne, and the smoke of the incense rose rose with the prayers of the saints from the hand of the angel before God” (Rev 8:3–4).

Black Legend

The unhistorical idea that aspects of Catholic worship, such as burning incense, are somehow pagan is part of anti-Catholic “black legend” propaganda that can still be found among the more fundamentalist Protestant denominations.

The basic gist of the black legend is that Christianity existed pure and undefiled for only a short time before pagan elements were introduced by an unholy alliance with Rome, forcing the “real Christians” to go underground only to reemerge after the Reformation. These claims simply don’t stand up to historical scrutiny. But this doesn’t stop people from mistakenly believing that certain Catholic practices — like burning incense and candles, or wearing vestments — are borrowed from pagan rituals.

Some of these claims are ridiculous on the surface. To suggest that since pagans burned candles and Catholics also burn candles means Catholics are participating in a “pagan ritual” is to ignore the fact that both Christians and pagans require light to see after dark! To borrow a line from G. K. Chesterton, “They may as well accuse us of having pagan legs!”

Pagan Christmas Trees?

Many of our beloved holidays are accused of being pagan, even holidays as blatantly Christian as Christmas — Christ’s Mass. How could a holiday celebrating the birth of Jesus possibly be pagan?

Well, take Christmas trees, for example. They don’t seem to have anything to do with Christ’s nativity. So why do we chop down evergreens and drag them into our living rooms every December? Could it be some lingering remnant of an ancient pagan ritual giving homage to forest spirits? Sounds plausible, right?

Except there is no historical evidence for that. The actual origin of the Christmas tree is not lost in the ancient mists of pagan Europe. Rather it comes from the very Catholic 12th century German tradition of putting on a Paradise Play every December 24. These plays depicted the story of the creation and fall of Adam and Eve, ending with the promise of the coming of a Savior. That’s why they were celebrated right before Christmas. These plays required one notable piece of scenery — the Paradise Tree. This was a large evergreen tree, decorated with bright red apples.

It soon became the custom to erect a paradise tree in individual homes as a reminder of our first parents, and to decorate them with apples and other ornaments — usually edible sweets. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, blown glass ornaments became popular.

The custom spread from Germany into other parts of Europe, and eventually to America. Queen Victoria introduced what by then was called a “Christmas tree” to Britain in 1841. Today it has become a universal symbol for Christmas. While, strictly speaking, it has nothing to do with Christ’s birth, its origins are definitely Christian rather than pagan.

A Solstice Festival?

Some claim that our December 25 observance of Christmas itself is of pagan origin. The argument is that Christians appropriated a much older pagan winter solstice festival. After all, we don’t really know when Jesus was born. So the early Church just picked the date to piggy-back off an already popular Roman festival.

Sounds plausible. Except that’s not how it happened.

But before we look into the origins of our Dec. 25 observance, let’s assume for the moment that the Church did choose this date to observe Christ’s birth because of the winter solstice. So what? Wouldn’t it be fitting to celebrate the coming of Christ, the light of the world, at that time of year when darkness begins to diminish and the days grow longer?

“The true light that enlightens every man was coming into the world” (Jn 1:9).

“The people that walked in darkness, have seen a great light: to them that dwelt in the region of the shadow of death, light is risen” (Is 9:10).

So what if pagan religions also held festivals around the solstice? Pagans and Christians lived under the same sun, did they not? They had the same powers of observation? May Christians not find meaning in the natural world around them without being accused of backsliding into paganism? God made the sun and the seasons, did he not?

Even if December 25 were chosen as the date of Christ’s birth because of the winter solstice, that wouldn’t make Christmas a pagan holiday. But, as it turns out, that’s not what happened historically.

Good Friday

Even before the Christians began celebrating the birth of Christ, they celebrated his death and resurrection. And they had an idea of when that happened. Ancient tradition had it that Christ died on March 25. And if Christ’s life ended on a March 25, the idea soon developed that it must have begun on a March 25. Jewish thinking at the time held that very holy people’s lives began and ended on the same day. It was thought to be a sign of their perfection.

But of course life doesn’t begin at birth. Even in the first century there was an understanding that human life begins at conception. And so the tradition took hold that the Annunciation of the Angel Gabriel to Mary occurred on March 25. And if Christ was conceived on March 25, then (being a perfect baby, neither early nor late) he would have been born exactly nine months later on December 25. And that’s the origin of our date for Christmas. It has nothing to do with the winter solstice and everything to do with Good Friday.

…Oh, and Sol Invictus, the Roman festival of the Invincible Sun celebrated on December 25? That didn’t come about until 274 AD when it was instituted by the Emperor Aurelian. So perhaps the pagans stole their celebration from the Christians!