There is a curious story recounted in the book of Numbers of a time when the people of Israel were being plagued by fiery serpents because of their rebelliousness toward God. The serpents were called “seraph” or “burning” most likely because of the painful burning of their venomous bite. To cure the people of this affliction, God instructs Moses to make a bronze serpent and mount it on a pole for the people to look upon. Whoever looked upon the bronze serpent, this image of the very thing that plagued them, would be healed (Num 21:4-9).

Like I said, it is a curious story. The image of a serpent is evocative of the tempting serpent in the Garden of Eden, so we can easily read into this incident a spiritual lesson about sin. But why would looking upon the very thing causing us pain provide a remedy for that pain? Some commentators have suggested this may be a kind of spiritual inoculation, where a small dose of the disease helps to bring about a cure. Perhaps there is something to that. But in any case, the incident of the bronze serpent remains one of the more curious episodes of Israel’s time in the desert.

And it is one that Jesus himself refers to when he speaks of his coming passion in terms of being “lifted up.” In John chapter eight he tells the Pharisees, “when you lift up the Son of Man then you will realize that I AM” (Jn 8:28). And in John chapter twelve he says that when he is lifted up he will draw all men to himself (Jn 12:32). John points out here that Jesus is talking about the kind of death he would suffer (v. 33). And to make the point even more explicit, in John chapter nineteen, which we just read, he quotes the prophet Zechariah in saying, “They will look upon him whom they have pierced” (Jn 19:37, Zec 12:10).

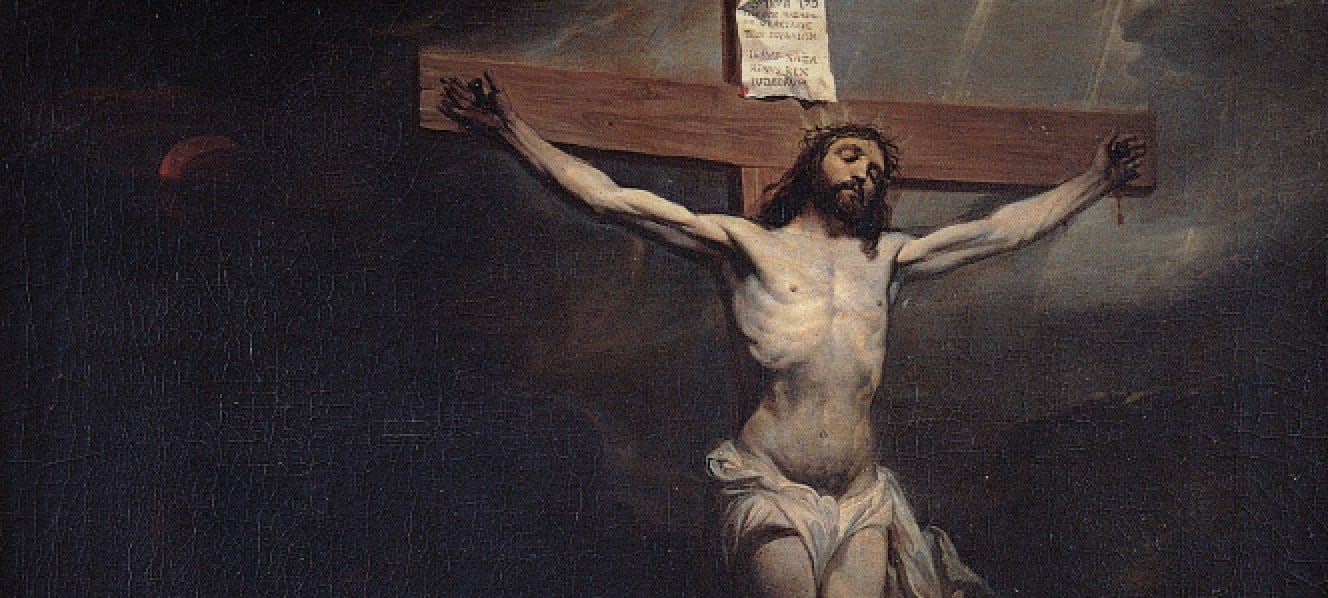

Just like the bronze serpent lifted up on a pole, Jesus is lifted up on a cross as the remedy for our affliction; not a burning snake bite, but the affliction that resulted from that very first encounter with a serpent, the spiritual disease of sin. But if the Israelites were healed by looking upon an image of what afflicted them, how does this work in relation to the crucifixion of Jesus, who is the Image of God? It isn’t God that afflicts us, but the separation from God brought about by sin. Jesus, the Image of God, would have to somehow also be the Image of Sin. It sounds odd, even blasphemous, to say that. Yet scripture tells us that is the very thing that happened.

Our first reading from the prophet Isaiah begins by saying God’s servant shall be raised high — or “lifted up,” in other words — but then goes on to speak of the ugliness that would mar his appearance (Is 52:13-14). It is not only the ugliness of the physical abuse he suffered, but the ugliness of sin itself. “It was our infirmities he bore, our sufferings he endured . . . he was pierced for our offences, crushed by our sins.” His bearing our sins would “make us whole . . . by his stripes we are healed” (Is 53:4-5).

This calls to mind the Old Testament practice of sacrificing a scapegoat on the Day of Atonement. In addition to the sacrificial offering made to God, on the Day of Atonement each year a second goat would be offered. The priests would lay their hands on this goat, symbolically placing upon it all the sins of Israel, and release it into the desert as an offering to Azazel, so that it might bear away the sins of Israel (Lv 16:7-10). The laying on of hands over the goat is evocative of the laying on of hands at priestly ordinations; for in fact, this is the role of the priesthood — to take upon themselves the sins of the people so that they might make atonement for them.

On the cross, we see Jesus acting as the great high priest, as mentioned in the Letter to the Hebrews (Heb 4:14), offering not a goat or a lamb, but his own flesh and blood in atonement for our sin. But unlike the scapegoat that represented the sins of Israel, Jesus actually becomes sin for us. This is how St. Paul describes it in his second letter to the Corinthians: “For our sake [God] made him to be sin who did not know sin, so that we might become the righteousness of God in him” (2 Cor 5:21). Jesus does not merely bear our sins, he becomes sin for us, so that we might become righteous. That the all-holy Son of God would become sin is a difficult thing to imagine, but if we fail to wrestle with this teaching, we will miss something of great importance.

One of my students recently shared a prayerful insight with. As she was praying the Sorrowful Mysteries of the Rosary, she asked what it could mean that Jesus became sin. The answer given to her is that our Lord became sin so that our sin might die on the cross. By his sacrifice on the cross, Jesus puts our sins to death. The offering Jesus makes on the cross is not just to bring about our forgiveness, but our sanctification. Jesus frees us from sin so that we might “go and sin no more,” as he tells the woman caught in adultery (cf. Jn 8:11). He wants us not only to be forgiven, but to be holy. Lifted up on the cross, he provides the grace to make that happen, so that by looking upon him who has been pierced, we might be cured of the curse caused by the ancient serpent, the devil, and restored to the dignity of children of God.