The Deacon as Divine Messenger

The identity of the deacon in the modern Church is a subject that fascinates me. Having been revived as a permanent order for only the past…

The identity of the deacon in the modern Church is a subject that fascinates me. Having been revived as a permanent order for only the past fifty years, after a long decline in the West, the ministry of the deacon is still something the Church is grappling with. The Church has much to say about the ministry of the priesthood, and increasingly since Vatican II has also thought much about the role of the laity. But the deacon is for many still a mystery. He is not an “almost-priest,” nor is he an ordained social worker, though this is how he is often painted. The deacon’s particular role in the Body of Christ is of great interest to me, not just because of my personal vocation but also because of my general interest in ecclesiology.

This summer I have begun reading Diakonia Studies by John N. Collins. The author is a linguist who has spent 40 years researching the nature and function of Christian ministry. This book is a summary of the research and argumentation he has made regarding the early Greek term diakonia. I am only about a third of the way through the book, and am already intrigued by his presentation.

Received wisdom is that diakonia and its cognates mean “service” or “servant” and therefore the primary role of the deacon is to be a minister of charitable service. I was surprised to learn that this particular understanding of the diaconate has relatively recent origins in a nineteenth century German translation of the New Testament — a translation that Collins argues is not true to the Greek sense of the word. In the fourth chapter of his book, Collins gives examples of the different ways ancient Greeks used the term diakonia. This is where the text began to get really interesting.

Even though the most common English translation of diakonos today is “servant,” none of the ancient Greek usage of the term denoted menial service or slavery. Instead, the term was used to denote a messenger or intermediary. Very often the word had religious connotations.

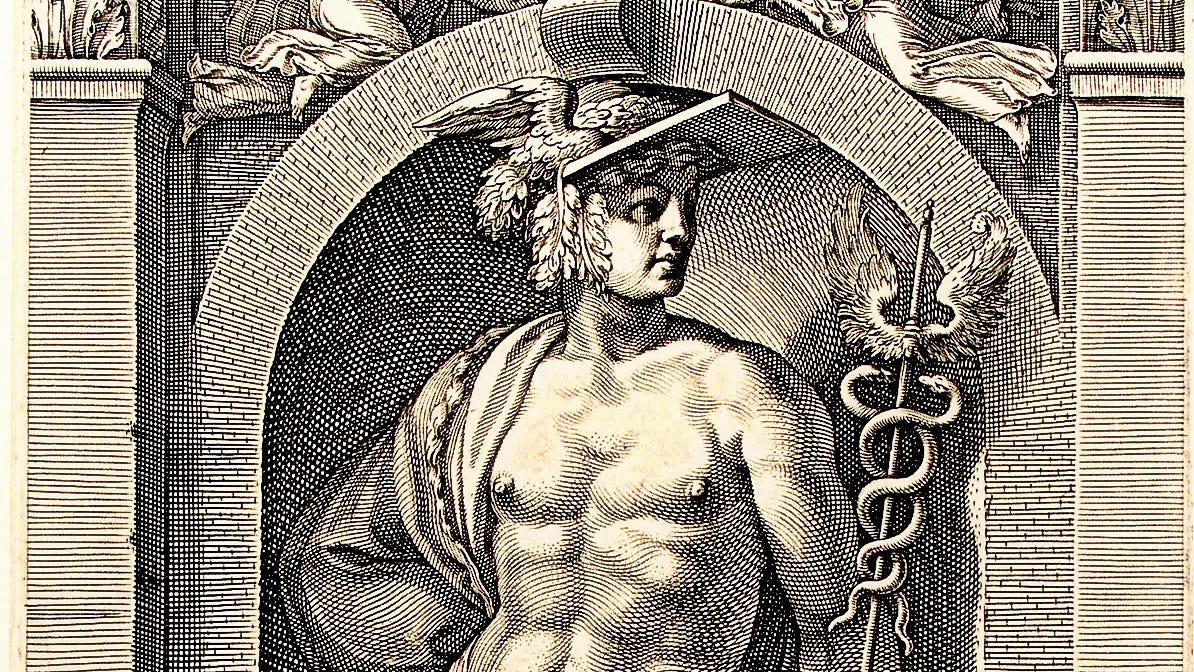

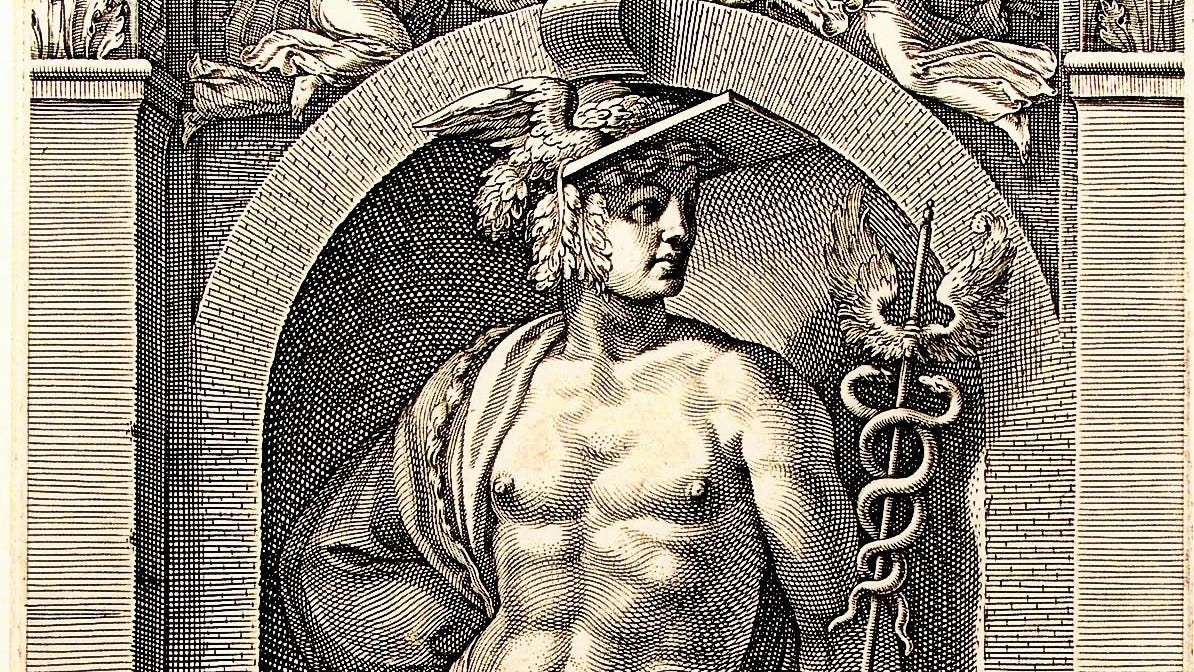

For example, the Greek god Hermes is called the diakonos or messenger of the gods. Lower gods or other spiritual creatures who carried out the work of the gods on earth were called diakonos. To the ancient Greeks, this word held the meaning of a divine messenger who carried messages between the gods, or back and forth between earth and the gods. It is very easy to see a parallel to our Judeo-Christian understanding of angels, which explains why the deacon has traditionally been associated with angels in Christian thinking.

Jewish writers who wrote in Greek used the term in a similar way. Collins references a text called The Testament of Abraham in which Abraham asks St. Michael to “be the medium of my word… unto the most High,” where the word translated as “medium” is a form of diakonos. The same term was also used to describe human prophets, whose role it was to be a mediator between the people and God. Collins argues that diakonia was the best way to indicate to Greek readers that “the prophet is about to engage himself in the religious business of getting messages to and from heaven.”

In non-religious contexts, the term still denotes an intermediary. Natural philosophers used the term to describe how air carries sound to our ears, or a glass lens focuses and transmits the light of the sun. In government, the term was used to denote ministers of state, who carried out the will of the ruling authority. In this context, Aristides wrote that “to minister (diakon-) for one’s superiors is man’s noblest and greatest capacity.”

What about waiting on tables? According to Collins, the Greek word diakonos was only used in relation to meal service in one specific context. He describes a ritualistic Greek meal called a symposion (literally, “drinking together”). The final course of the meal consisted of wine and had religious connotations. Collins writes:

This was an occasion not just to indulge but to celebrate wine, the gift of the gods. In fact, the first wine of the night was poured out in tribute to the gods. The wine was always mixed with water, the mix being at the discretion of the host. The symposion had a ritual air to it and was very ancient.

The cupbearer at this ritual meal, who poured the wine mixed with water in tribute to the gods, was never a common servant or member of the household slave staff. The cupbearer was chosen from among the sons of free men. It is only in this context that Collins finds diakonos used to describe what we would call “table ministry.” The parallels to the function of the Christian deacon at Mass are striking.

The rest of Collins’ book covers use of diakonos terms in the gospels, in Paul’s writings, and in Acts. I plan on finishing the book in the coming weeks, and may have more to say about it. Even just getting this far through the book has given me a better perspective on how Greek speakers two millennia ago would have understood diakonia — as divine messenger, intermediary, and minister of the cup. These meanings would have been in the minds of the inspired authors of the New Testament, and perhaps even the Apostles themselves, when they chose this word.

Deacons are conveyors of a divine message. They are ambassadors of the Apostles, who themselves are ambassadors of God. This is why the deacon has the privilege of proclaiming the gospel and preaching in the assembly. This is why the deacon has the solemn duty to teach the faith in word and deed. He is a prophet who speaks on behalf of another. His is an angelic ministry. I am reminded of how the angel Gabriel is often put forth as a model of diaconal ministry; he brings God’s word to Mary and returns to God with Mary’s response. The deacon brings into the world the word of One much greater than he, a word which is not his own, but a word to which he is bound.

Read the second part of my commentary on Diakonia Studies here:

The Ministry of the Deacon

Last June I wrote about “the Deacon as Divine Messenger.” I was in the middle of reading Diakonia Studies, by John Collins, a linguist specializing in early Greek. My commentary there focused on how the term diakonia was unde…