The Ministry of the Deacon

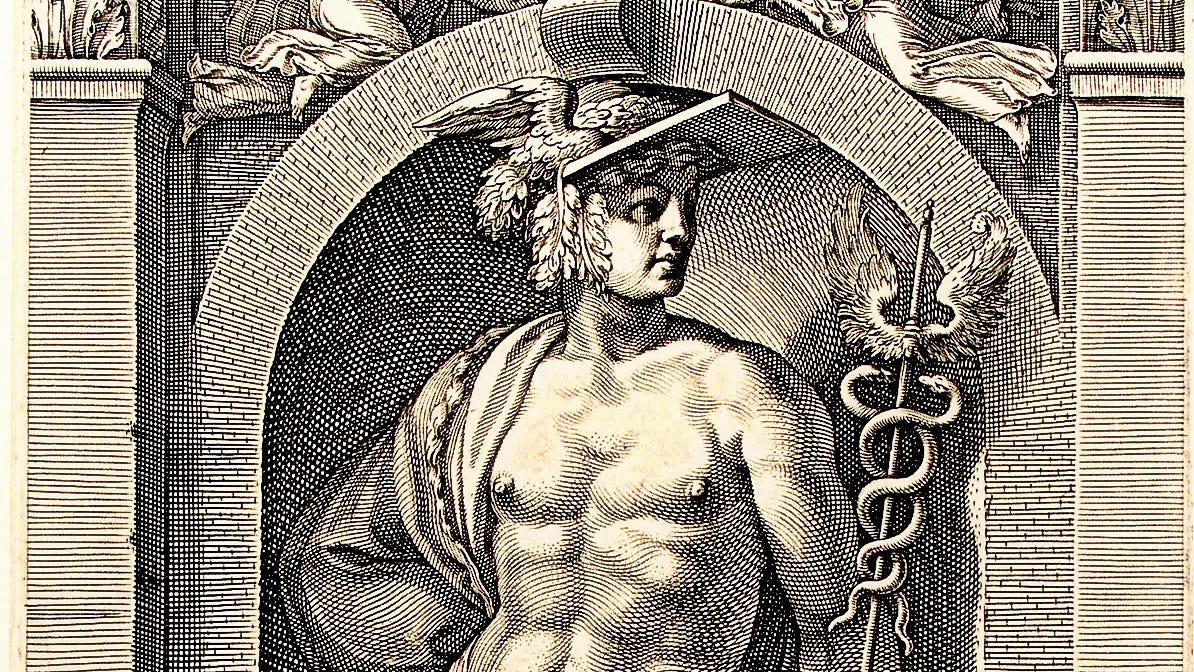

Last June I wrote about “the Deacon as Divine Messenger.” I was in the middle of reading Diakonia Studies, by John Collins, a linguist…

Last June I wrote about “the Deacon as Divine Messenger.” I was in the middle of reading Diakonia Studies, by John Collins, a linguist specializing in early Greek. My commentary there focused on how the term diakonia was understood by Greek speaking people before and during the time of the New Testament. To Greek speakers, it meant a messenger or intermediary, especially one who conveyed divine or heavenly messages. It could also mean an ambassador or government official — one who spoke and acted as an official delegate of a higher authority.

While the first part of Collins’ book deals with how the Greeks understood diakonia, the middle part of the book looks at how diakonia is used by the New Testament writers. The final part of the book looks at how modern concepts of diakonia have implications for our understanding of ministry in the Church today.

Acts & the Ordination of the Seven

I want to focus here specifically on the use of diakonia in Acts. Acts chapter 6 has special significance for every deacon as it tells of the ordination of the first seven deacons (I have written some about that here). But it also raises certain questions. A cursory reading of most modern English translations suggests that the Seven were ordained by the Apostles to “serve at the tables” of Greek speaking widows. But why ordain someone just to oversee food distribution? This is an important task, but surely not one requiring Apostolic ministerial faculties.

Then there is the fact that we never actually read about these deacons serving at tables. Luke goes into detail about the activities of two of the seven, Philip and Stephen. He describes them preaching, teaching, baptizing, and dying as martyrs. But he never mentions them waiting at tables or distributing food. It seems odd that this would be entirely left out of Luke’s account of their ministry if this was the very task they were ordained to do.

What Collins suggests, by looking at Luke’s original Greek, is that they were not ordained to serve at tables at all; that this is a misunderstanding based on faulty translations. The word diakonia appears three times in this passage, in verses 1, 2 and 4. I will insert the Greek word into the NAB English translation to show where it occurs.

And all day long, both in the temple and in their homes, [the Apostles] did not stop teaching and proclaiming the Messiah, Jesus. At that time, as the number of disciples continued to grow, the Hellenists complained against the Hebrews because their widows were being neglected in the daily diakonia. So the Twelve called together the community of disciples and said, “It is not right for us to neglect the word of God to diakonia at table. Brothers, select from among you seven reputable men, filled with the Spirit and wisdom, whom we shall appoint to this task, whereas we shall devote ourselves to prayer and to the diakonia of the word. (Acts 5:42–6:4)

Collins then reviews the other times Luke uses the term diakonia. The word first appears in Acts 1:8 and 1:17, in reference to the Apostles selecting a replacement for Judas in their ministry (diakonia) to be witnesses of the gospel. Later in Acts 20:24 and 21:19, Luke uses diakonia to describe the ministry Paul received from Christ to be His witness. When Luke uses diakonia it is always within the context of the mission (ministry) received by Christ to be His witness, spread the gospel and/or make disciples. Acts 6 is no exception.

Collins argues that the “daily distribution [diakonia]” the Hellenist widows were missing out on was not their share from the food pantry, but their share in the preaching of the word. As foreign widows, they were likely among those being preached to in their homes (see Acts 5:42), perhaps around the table during a ritual meal (the breaking of the bread). Greek speaking men of faith were chosen to go and preach to them in their own language. Meanwhile the Apostles would continue their diakonia by preaching in the temple, where the larger number of people would be gathered.

This explains why the Seven needed to receive a share in the Apostolic mission by the laying on of hands. It was not so that they could distribute food. Their ordination made them participants in the ministry (diakonia) the Apostles received from Christ. The passage describing the ordination of the Seven is book-ended by statements about the word of God spreading and the numbers of disciples increasing (Acts 5:42–6:1, and 6:7). This is the context in which we are to read this passage. This is the business — the diakonia — that the Seven were ordained to do.

The Meaning of “Ministry”

This reading of Acts 6 gives a sharper perspective on the role of the deacon as an ordained minister of the word, liturgy and charity. It also has made me more aware of how dependent we are on translations, which can be imprecise. In the last part of his book, Collins addresses the concept of “ministry,” which is a common English translation of diakonia.

This single English word can signify charitable service (as in a nurse ministering to her patient) and an office of authority (as in the British government). But other languages lack such a word. Collins gives the example of German, where Amt (office) and Dienst (service) have meanings that are not only different, but dichotomous. Which one is used to translate diaconia will yield radically different understandings of diaconal ministry — which is just what Collins argues happened with certain German translations of the nineteenth century, the influence of which has resulted in confusion about the diaconate and ministry in general throughout the Western Church.

In summation, I have found Collin’s book very helpful for clarifying in my own mind the special character of the deacon as a minister of the Church. I wouldn’t necessarily recommend it in its entirety (the beginning chapters were tedious and there is a chapter at the end in which he suggests the possibility of women’s ordination) but the “meat” of the book dealing with the linguistics is something I think anyone interested in the diaconate would benefit from reading.

Read my thoughts on the first part of Diakonia Studies:

The Deacon as Divine Messenger

The identity of the deacon in the modern Church is a subject that fascinates me. Having been revived as a permanent order for only the past fifty years, after a long decline in the West, the ministry of the deacon is still something the Church is grappling with. The Church has much to say about the ministry of …